Cleveland Experience

In my poem Prairie God (1966) and book The Emerald Tablet: Alchemy for Personal Transformation (1999), I describe a monadic experience I had in 1952, when I was 7 years old.

In my poem Prairie God (1966) and book The Emerald Tablet: Alchemy for Personal Transformation (1999), I describe a monadic experience I had in 1952, when I was 7 years old.

Our family lived in one of those red-brick tenement houses in South Chicago, and my mother had taken me to a free clinic to get a polio shot. I distinctly remember how filthy the clinic was, and the mangy old dog they let wander around. I also remember how angry the burly nurse was when she came in to give me the shot. She was so upset (why I do not know), that she jabbed the 2-inch needle viciously into my rump, and it got stuck deep in my hip bone. She had to use a pair of pliers to pull out the needle. I’m not kidding—this really happened.

To make matters worse, hepatitis developed in my bone marrow from the unsterile needle. Within a few days, my liver swelled to seven times its normal size and started interfering with the functioning of my other organs. It was pressing against my diaphragm, and it was impossible for me to take a full breath. The doctors told my mother I had a fifty-fifty chance of surviving.

After three months of trying to fight off the infection, I had no energy for even the most trivial activity and started looking like a dying person. My skin had a yellow-gray hue, and my eye sockets were sunken and dark. Inside, I was experiencing the death of my nascent ego, and I became passive and withdrawn.

Then, thankfully, my parents moved from South Chicago to the prairie in Blue Island, Illinois. By the time we got settled in our new home, there was not much left in the world I really cared about, and maybe that is how I became sensitized to other things.

I was transfixed by being in raw Nature and spent hours walking alone in the extensive prairie land behind our house. Being outdoors in the Sun brought me back to life. And for some reason, I started drinking the cloudy white, bitter sap of milkweed thistles and chewing the leaves, even though I was warned repeatedly it was poisonous. Years later, I learned that the plant is the source of silymarin, which is a liver restorer. So close was I to Nature.

One day that summer, a swirling breeze kicked up in our backyard, and I decided to playfully follow it. I cannot even say with certainty that I was following the same breeze all the time—it was just a game. Anyway, the gentle wind led me to a dirt path that went deep into the heart of the prairie. As I walked along the path, the plants and bushes along it suddenly started glowing and intensifying in color. I remember pausing and wondering if this iridescent display was just something in my head or if other people could see it too.

I continued along the path following the warm breeze, when I came to a gaping hole in the ground in front of a solitary, old oak tree. There was no reason such a large hole should be here in the middle of the prairie. How it got there, I had no clue, but the hole exposed the flesh-colored clay to a depth of about eight feet. The earthy smell was so strong that it tickled my throat. Yet there was something beguiling about that hole. I stood teetering at the edge for the longest time.

To this day, I am not sure what happened next. It was as if there were two great holes—one in the ground and another in me—and by our similarity, we merged into some sort of all-encompassing “cosmic hole.” Then, the yellow clay walls of the hole appeared to give off a faint golden light. I did not question a thing I was seeing; it all seemed to be occurring quite naturally.

But then the light was all around me, and it felt like this golden light was all there was anywhere—just this translucent light. The space around me had changed, and I was being “enfolded” by it. This did not seem natural at all. For the first time since entering the prairie that day, I was afraid.

As I stood on the edge of the precipice, I was torn between wanting to run away and wanting to jump in the hole and disappear into this deep new mystery. I started trembling from the enormity of the experience, when from out of nowhere, I heard my mother’s voice calling me. It could not have been her, since I was miles from home, yet I heard her yell my name, fetching me home, offering the comforts of television, dinner, and Dad.

I yanked myself from the edge of the hole and felt my body running as fast as it could until I reached home. In one giant leap, I jumped from the back door into the center of the kitchen, but my parents thought I was just playing and totally ignored me. I wanted to shout out what happened, but I never said a word to anyone because there was no way to put it into words. Plus, for some reason, I felt I had done something wrong.

I spent a lot of time thinking about the experience and trying to find a logical explanation. Was I hallucinating from too much milkweed? Did I suffer an epileptic fit or transient ischemic attack of some kind? Did I have a brain tumor? Was I suppressing memories of being molested or even abducted by someone or something? Was I going insane? Did I have some sort of near-death experience? Or was it just a kid’s overactive imagination?

The biggest question was, what if I had let go at the edge and jumped into that “cosmic hole”? Would I have entered some new dimension or been absorbed into nothingness? Or would I have merged with the golden light that seemed so safe and warm? Or would I have lost my mind?

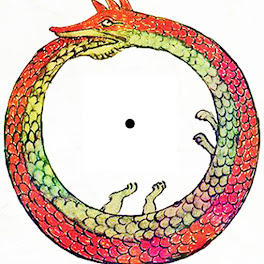

One odd feeling that stayed with me after the experience was the nontangible sense of “eightness” or “Eightspace,” as I later came to call it. This was the central mystery of the event that has stayed with me all these years. I can still feel the enigmatic sensation of “twisting” into a different kind of space—something based on eightness, not the four-square cubic space of which I was accustomed.

I spent years researching the mystical and paranormal experiences of others and discovered a lot more questions than answers. I realized that encounters like mine were fundamental human experiences shared by people from around the world. The problem is that the phenomenon is so deeply rooted in our minds that it is nearly impossible to face it objectively. Nearly everyone takes a position based on their academic training, psychological history, or religious backgrounds. Fortunately, I was too young to have any framework into which to mold the experience, so I just accepted it “as is.” Any objective explanation I found for the experience corrupted it—it had to be experienced to be understood.